Clinical Networks Part 2: Gardening

- Allan Wardhaugh

- Aug 13, 2024

- 9 min read

This is the second in a series of three blogs describing why and how we decided to reform existing Clinical Networks in NHS Wales. They are personal reflections on the process I undertook with a number of colleagues, listed as authors in our final paper. I am also grateful to Professor Sally Lewis, former National Clinical Director for Value Based Healthcare (VBHC) in Wales for several years’-worth of idea sharing and formative conversation which informed this work.

The ask and the tell

At the beginning of work on the National Clinical Framework, we were told that the system needed to change, and the work we were leading ‘needed to be transformational’. There was a ‘but’ though. Its form was of the ‘you can’t start from scratch’ variety.

There was consensus from stakeholders that the model described in part one, of National Clinical Networks having an integral role in setting direction and informing accountability for the health system at national level was logical. We had drawn from much of the positive work we were aware of which was happening in the Clinical Networks as they were then (now legacy networks), but we were also aware that there were many problems too. In a couple of early conversations with government and other stakeholders, we floated the idea of wiping the table clean and rebuilding networks, but the clear message in return was we would not be allowed to do that and must instead build on existing. We did not think this unreasonable, although were also frustrated that we were receiving mixed messages. Give us something transformational and radical – the language in A Healthier Wales was a ‘revolution form within’ – but don’t rock the boat. At the same time, there was much that was happening in Clinical Networks that we thought ought to be preserved and developed. The tension between transforming and destabilising never goes away, and in healthcare a 'move fast and break things' approach is not usually sensible.

Before embarking on a description of the legacy environment, it is worth emphasising that the overwhelming impression we had of work happening in the legacy networks was positive. Some were already employing a Learning health and Care System model, without necessarily labelling it as such, and with little supporting infrastructure to help. Many had embraced Value Based Healthcare; many had a multi-professional establishment with good third sector involvement and patient group representation. There was enough to build on, and the negatives were surmountable.

Legacy Networks

What was the Network landscape? What were Clinical Networks? What Clinical Networks existed? How did they fit in with the governance system?

The untidy garden

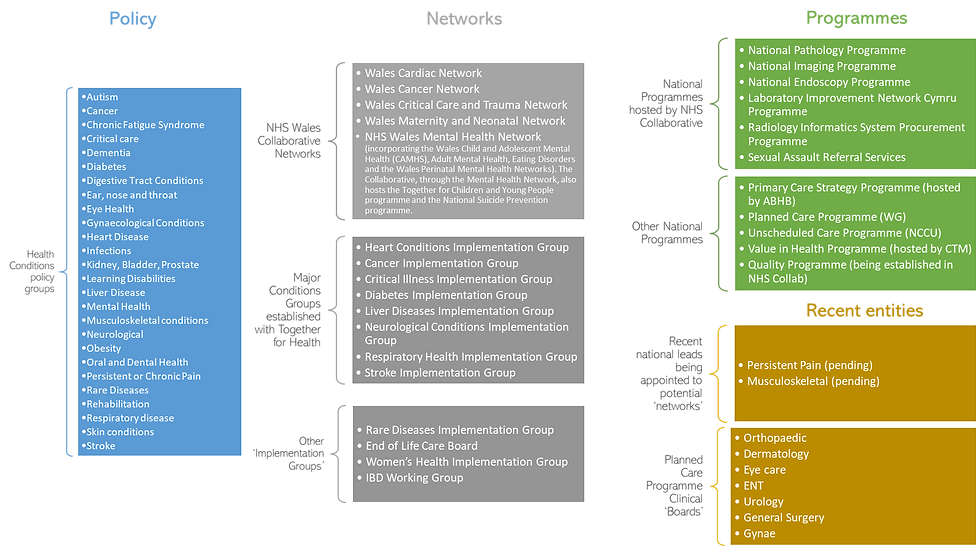

Trying to formulate a conceptual map of National Clinical Networks was challenging. There didn’t seem to be a definition for the networks that existed, and nor were there consistently clear governance connections with Health Boards or Government. Figure 1 shows a representation of the landscape in 2022 when implementation of the National Clinical Framework was starting.

Fig 1. A schematic of Clinical Networks and other similar entities in 2022

There were some entities called Networks, not all of which seemed to actually have a network. There were some formally established entities called Implementation Groups which were often referred to colloquially as Networks (including by their members), but there were other Implementation Groups which existed outside that establishment. Some of Clinical Networks and Implementation Groups had programmes of work, and some of those would be referred to colloquially as ‘National Programmes’. Confused? Most people were.

There was also a collection of ‘National Programmes’. Some of these looked a bit like ‘Clinical Networks’. Some of the formally established National Programmes were hosted and run from government, some were done so from different Health Boards. Some were very big and ambitious (perhaps over-ambitious), others very small, but seemingly achievable.

It was a dynamic situation. New entities were still appearing in what we characterised as ectopic activity (se below), and it felt like this was increasing as talk of change and reform grew louder.

There is much more nuance and detail behind this which I could go into, and is instructive on many levels, but that is for the nitty gritty of consultancy rather than here.

The overall impression was of a garden that had got a bit out of control. There was no doubting the good intent displayed in the establishment of nearly all of these entities, and there did seem in many instances a good plan for how bits of the garden would be planted. Over time, however, some of the shrubs had bolted and taken the light from other shrubs which then suffered, some weeds had appeared – often pretty, but not part of the plan – and the whole thing had become very messy.

The opportunity here was to do some pruning, weeding and replanting to get the garden looking nice – building on existing, not starting from scratch. The central guiding hand of a gardener perhaps. Better still, a team of gardeners working to a common vision.

Ectopic activity

A special word on this phenomenon, which may explain some of the weeds in the garden. The term weed is not intended to be pejorative, but it fits with the metaphor. If we accept the definition of a weed as a beautiful and useful plant, but one out of place, then it's apparent there is no need for Round Up, it's more a question of re-locating.

Many entities seemed to have been created by a desire to respond to an issue of public and political concern by ‘doing something’. This something often seemed to be by bringing into existence a ‘Network’ or a ‘Programme’ which was intended to address the issue. What seemed to be missing often was a filter where someone or some group was able to suggest that the intended issue could actually be addressed by an existing network or programme, or at least be incorporated into some existing network. Duplication could occur where two or more entities were being tasked to address essentially the same problem.

This ectopic activity was frustrating for those trying to address their issue. They felt isolated, disconnected and were often unsure how to navigate the system. They were also not connected to any clear governance structures whereby their outputs could be effected or managed. At worst it could feel like box-ticking or tokenism.

Another opportunity for a central guiding hand.

Function

For many of the entities above, there was a lack of clarity in what they were for. In some, there were terms of reference that would at least touch on function, but it was not always clearly defined, and in many cases seemed to have been subsumed by a different agenda.

Some had money to spend and a bit of influence, some had money but no influence. Some had no money, but a bit of influence, and some had neither. What money was spent on varied greatly and it was not always clear that the governance and decision-making was aligned to system priorities.

There also appeared to be a lack of consistent oversight, unclear strategic alignment, almost no tactical alignment to other initiatives. The relationships between National Programmes and the formally established Clinical Networks and Implementation Groups was not always evident, and what cross-communication did exist was ad hoc.

Some of the entities had morphed into lobby groups, with no sense that they were part of a wider collective working within severe financial constraints. Although there were welcome links with third sector organisations in many of the networks, this did sometimes seem to partly drive the approach. Some within the networks felt this was what networks should exist to do, but it was clearly not consistent with the approach outlined in the National Clinical Framework.

Form

Many of the entities had established ‘Boards’. In fact, that was often the first action in their establishment. An oft-repeated maxim encountered during this work was ‘form follows function’. The opposite seemed to occur in most circumstances. Some of the Boards had developed reference groups and subgroups, which had themselves become quite complicated. Most simply had a board, sometimes doubling as a reference group – but often just existing for all practising purposes as a board.

For almost all groups, colleagues from secondary care predominated. Even when there were members from primary care or other sectors, the agenda tended to be dominated by secondary/ tertiary care issues or a secondary/ tertiary care perspective. This was not universal, however, and even in some networks that had a predominantly hospital-based establishment, there was a huge focus on primary and community care and a desire to engage with other care sectors. What was missing in those cases were enough people from those sectors willing or able to participate.

Doctors tended to predominate, especially as Clinical Leads for the groups. A couple of networks had a much broader base of Allied Health Professionals, but ironically that did set up some inter-professional tensions: those networks seeing as being ‘for therapists’, and others being ‘for doctors’.

A common observation, and a common admission by Network members was that their agendas and work formed a mix of Strategic, Tactical (Projects, research, Proof of concept) and Operational – all at the same time, no delineation. There was a sense of members feeling the need to do everything, everywhere all at once. Many felt they had been sucked into a role as operational trouble shooters – but without having the teeth do actually make things happen (more on ‘teeth’ in a minute).

There was a National Clinical Leads group, but it met irregularly, its membership was not clearly defined and its outputs were not connected to anything systematically. Not surprisingly, morale in this group was patchy.

Outputs

Some of the Networks and Programmes with money to spend could point to ‘outputs’. The frustration was that the outputs were seldom truly national in scale. Where some national changes had been achieved, it had been difficult and exhausting according to those involved.

Most of the tangible outputs seemed to be in the form of ‘proof of concept’ projects. There was great frustration in that these often were impossible to scale up to national level. It also appeared true that there seemed to be an expectation from some stakeholders that the move from proof of concept to national ‘roll-out’ was a simple one-step procedure. In many cases the context-specific nature of the project were underplayed, and the need for an iterative and more gradual implementation at national level might be required. But even where there had been an approach on these principles, and agreement that a concept had indeed been proven, there was no mechanism to enable a concerted and co-ordinated national approach across 7 Health Boards.

Some of the outputs were in the form of evidence-guided clinical advice, or even better, evidence-guided clinical pathways. But again, the lack of ‘status’ within the governance system seemed to be the constraint. There were several well designed and thought through pathways that were suposed to have been adopted nationally, but to the immense frustration of their authors, few had.

Status

This lack of status was the biggest frustration among clinical leads and their network members. Not because they desired status for its own sake, but because they felt had little power to influence.

The overall feeling was they were not always taken seriously, there advice was either disregarded, or incompletely implemented.

The view from Health Boards was that Clinical Networks were not always representative of all of their colleagues, were often dominated by a secondary care perspective, frequently seemed to be lobbying for special interests, all without an understanding of the wider system pressures. It was usually difficult to argue against this view in most instances.

Clinical Networks tended to be focussed quite narrowly on their agendas, without being aware of what was happening elsewhere. The Health Boards are in a much better position to understand competing priorities in their organisations, and practical constraints in implementation.

It is also true that the Health Boards were required to be focussed on their own population, geographically defined. This runs counter to developing regional solutions, or agreeing to conform with a national position that might be difficult for an individual Heath Board to comply with. The complexity of the arrangements of clinical groups outlined here mean they could not be aware of all that was happening at national level. I have not even touched upon the large number of arms-length organisations established by Government and by individual Health Boards which produced another layer of complexity. Achieving a helicopter view of all of this was challenging enough for my colleagues and I and we had the time and space to do it: it seemed impossible for Health Board Executives who had more than enough to keep them occupied in their bases.

How to foster better and more collaborative relationships between Clinical Networks and Health Boards became the dominant issue for us. But in order to even strat to address that, it was clear we needed to reform the Clinical Networks themselves.

Reforming the Networks

All of the above established a case for change, bringing Clinical Networks into the Central Guiding Hand function (the NHS Executive). The Executive could develop the helicopter view of a complex environment, at the same time tidying it up, ensuring better strategic and tactical alignment across health Boards and Arms-Length Organisations.

In order to play their part as the clinical guiding hand, the networks would need to have more clearly defined function, a form which enabled them to exercise that function, and in return they would have a place in the governance structure that gave their outputs a weight in the system.

I'm not going to blog about that, because the resulting networks paper explains what the suggested new networks would be, and how the problems articulated here would be addressed.

Next time

In the final part, I will look to the future; the opportunities and threats to National Clinical Networks, and to completeing a successful implementation of the National Clinical Framework.

I’ll talk about clinical leadership, clinical engagement vs clinical endorsement and the balance between having ‘teeth’ and exercising a stronger guiding hand. I'll wrap up by explaining why I wanted to blog about all of this.

Comments